Carrie Mulligan strikes a righteous #MeToo blow in incendiary rape-revenge fable

Promising Young Woman

Starring Carey Mulligan

Directed by Emerald Fennell

R

In theaters Dec. 25, 2020

A candy-colored rape-revenge fable with a fierce performance from Carey Mulligan, Promising Young Woman brings the righteous fury of the #MeToo movement into savagely wicked focus.

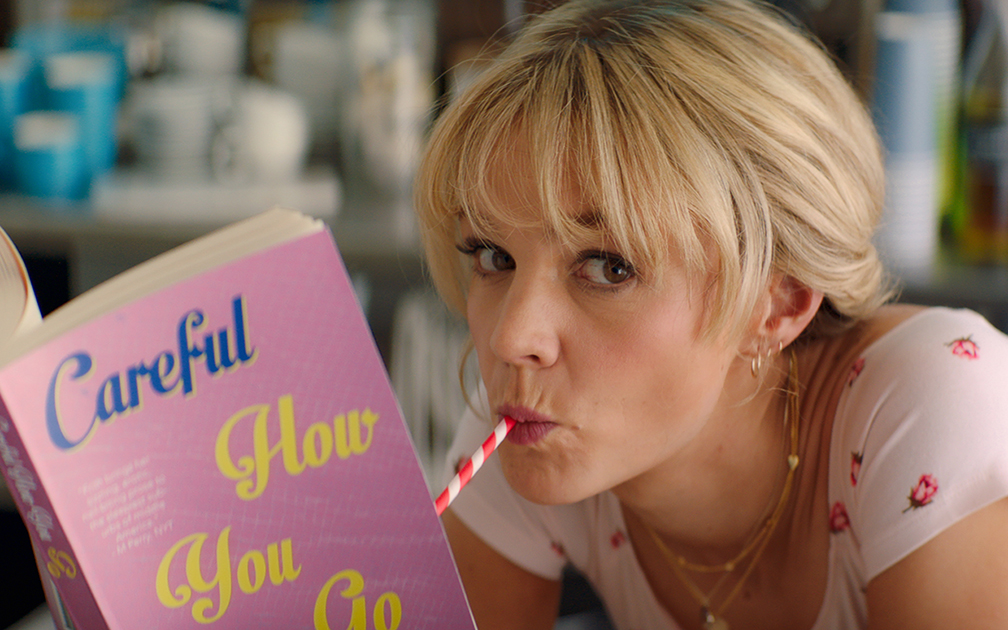

Mulligan stars as Cassie, a college dropout on the cusp of 30 who was once on track to become a doctor before a tragic event derailed her plans. Now working as a coffee-shop barista by day, she has a very different agenda at night.

In the evenings, she daubs on lipstick, dolls up and pretends to be sloshed in bars or nightclubs, just waiting for a so-called “nice guy” to offer to give her a lift home. When the ride invariably takes a detour and they end up at his apartment, and he ends up pouring her even more drinks, pawing her body, putting his hands down her blouse or up her skirt, Cassie abruptly turns out to not be nearly as sloshed as he thinks. Not sloshed at all, in fact.

The guy gets a shocking comeuppance, and Cassie gets to make another neat little color-coded hash mark in her book. Check!

Making her feature directorial debut, Emerald Fennel is already a hot property in Hollywood, as an actor (she played Camilla Bowles in The Crown), writer, and for her pair of Emmy nominations as executive producer and showrunner for the second season of BBC America’s Killing Eve.

You can see how Killing Eve—about a British intelligence officer who relentlessly pursues a psycho assassin to the point that the two become obsessed with each other—funnels into Promising Young Woman. Cassie is driven by her own obsession, too.

The event that derailed Cassie’s life involved a horrific act of sexual violence inflicted on one of her med-school classmates, her childhood best friend, Nina. There were other people involved, too—boys who afterward went on as if nothing had happened, keeping their nice-guy appearances and their reputations intact for the rest of the world. And there were those who knew what happened but didn’t do anything about it, or defended the guys, or even worse, blamed or discredited Nina…

The devastating incident destroyed her best friend, and it also crushed Cassie. It also galvanized her into a mission, setting her on a singular, obsessive path as a bait-and-switch avenging angel for every “promising young woman,” like Nina, who’d been victimized by acts of non-consensual aggression, who never got the justice they deserved.

Mulligan, so good in everything she’s ever done—from Pride and Prejudice (2005) to An Education (2009), Drive (2011), Inside Llewyn Davis (2013), Mudbound (2017) and Wildlife (2018)—is terrific here in a bold, boundary-pushing performance as an exhilarating anti-heroine: edgy, dark, dangerous, sexy, sad, wounded, wild, wily, self-aware but also scarily unhinged. She makes us feel the trauma that’s never left her, the fire that will never go out, a hurt that won’t heal, a hunger to stand up for something that so many women have had taken from them and can never get back. It’s powerhouse acting that fires on all lipstick-smeared, bruised and broken cylinders.

And it’s not just men that come into Cassie’s crosshairs. Even females can need some education in the matter.

“Don’t get blackout drunk…and expect people to be on your side when you have sex with someone you don’t want to,” says one of her former university friends (Alison Brie).

Alfred Molina plays an attorney haunted by what he did. Connie Britton is the dean who dismissed things as just another “he said/she said” matter. The OC’s Adam Brody, Christopher Mintz-Plasse (Superbad) and Max Greenfield (The Neighborhood) are all aboard, as (nice) guys who attempt to coerce Cassie into sexual encounters but don’t seem to think what they’re doing is inappropriate…and they certainly wouldn’t call it rape. Familiar, friendly faces, characters we recognize and maybe even feel like we “know,” in situations that turn into something abhorrent—just like we’ve all heard about happening in college dorms, apartments, or hotel suites…

Rape… predators… revenge… Those are all serious words and serious things, but Fennel deftly steers Promising Young Woman along its prickly path with deliciously dark humor, giving its gritty truths a hyper-stylized swirl of girly, candy-cane colors and a swish of vampy camp. Cassie’s on-the-town trolling outfits are so over-the-top, it becomes a dishy delight to see what she’s going to wear next—and what she’s going to do. Scenes with her barista boss (Orange is the New Black’s LaVerne Cox) have a snarky, sitcom-y snap. The movie veers into a kind of romcom sweetness when Cassie meets up with an old med-school classmate (Bo Burnham), now a respectable pediatric surgeon, whose puppy-dog crush on Cassie may reveal him to be the genuinely nice guy he actually seems to be.

But make no mistake about it: This is about men who do things they shouldn’t be doing, and get away with it, and a system that mostly enables and protects them. It’s impossible to ignore the film’s real-life backdrop—the rising chorus of #MeToo voices across the land in response to high-profile allegations and lawsuits against entertainment moguls, corporate giants, TV network execs…even President Donald Trump, who has been accused of sexual misconduct by at least 26 women, all of whom he has denounced as “liars.”

When Cassie gets out of her car and takes a tire iron to a guy’s pickup truck to teach him to mind his disrespectful mouth, she’s striking a blow for every woman who’s ever been called…well, you can guess the words. She’s striking a blow for every female who’s every been brave enough, bold enough, to step forward and tell how she’d been victimized by a guy who did something terrible, something awful, only to be dismissed and debunked, smeared and scorched…and then had to watch him go on to become a doctor, a lawyer, maybe even a U.S. Supreme Court Justice or a president.

“I didn’t do anything wrong!” one of Cassie’s transgressors tearfully tells her. “We were kids! We were all drunk!”

It all full-circles to a blowout bachelor-party finale that will leave you quite breathless as Cassie brings some closure to her mission—if not in the way you might be expecting.

Arriving in theaters on Christmas Day, Promising Young Woman isn’t quite It’s a Wonderful Life, A Christmas Story or Miracle on 34th Street. But if you’re up for a smart, sassy, stinging #MeToo kick to the chestnuts, I promise you’ll be thinking about it long after the eggnog is drained dry and the holidays are over.

Think about it: That’s what Cassie would want, after all.